4 de junio de 2020

Enforcement of Annulled Awards

Under the article V (1)(e) of the New York Convention, can the award be enforced in another country where it was made, when the courts of the country of origin set aside the award?

No, if the award was set aside in the country of origin, it can no longer be enforced elsewhere because immediately the award ceased to exist and therefore there is nothing to enforce.

According to Art. III of the Convention, courts have the obligation to enforce awards. However, I believe that this is a presumption that could be rebuttable. Art. V(1)(e) talks about the possibility that courts, from the place where the award was rendered, have to set aside the award. From the interpretation of the article V(1)(e), several theories have been born. One of those theories is the “Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit”, which is a philosophical expression that literally means “out of nothing, nothing [be]comes”. Base on this theory, drafters considered that if the award had been set aside in the country of origin, it can no longer be enforced elsewhere1. I totally agree with this position. Some participants in international commercial arbitration totally disagree with the “Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit” theory, among other reasons, because:

- They have long recognized the need to maintain arbitration as an effective and therefore attractive alternative to litigation2 ensuring the award is part of the consent. They believe that the application of the Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit theory will destroy the base of the arbitration that is the consent of the parties to go to arbitration and have an enforceable award;

- They affirm that the Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit theory gives “too much power” to the courts of the seat, they argue, that for example, in Yukos the Russian court set aside the award without any legal fundament, as same as in Pemex case and the court of Mexico.

- They are concern about instances where awards are set aside on grounds of national public policy which have no legitimate place in international arbitration, and rather seem the product of a desire to protect local interests3

However, I disagree with the above statements for the following reasons:

1. Regarding the first argument, and the importance of the parties’ consent, I would like to say that is different the idea to stopping the enforcement of an award under the New York Convention and to set aside the award. The New York Convention duties do not include setting aside. Setting aside is under the lex arbitri of the place of the arbitration. This distinction is of vital importance to me because it is the base of the sustention of my view of interpreting the Art. V(1)(e) according to the Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit When the parties select the seat of the arbitration and therefore the lex arbitri, the parties are expressing their consent, which is the base of the arbitration, to be subject in the future to the courts of the place. Nobody is imposing that decision. Consequently, they must assume the consequences that the selection of the seat carries, that is the possibility that the courts of the origin of the award set aside or “destroy it” if there are legal and reasonable reason to support the decision. Consequently, it can no longer be enforced elsewhere.

2. Regarding the second argument about “giving too much power to the courts of the seat”, I asked myself: Is not it giving too much power to the judges of the other countries to give the possibility to enforce an award that was setting aside in the country of origin? See the Putrabali case for instance, where unfortunately French courts were not aware of the provisional nature of the first-ier decision presented for the enforcement and they just enforced the award. Other example is Pemex case, where the US court applied a doctrine base on a “public policy gloss” of the Article V(1)(e) that enables courts to disregard an annulment judgment if that judgment violates the US most basic notions of morality and justice4. What is the US morality and justice? Is not it to board? Is not it “too much power” to other courts? Not to mention Yukos case, in which the Dutch court said that recognition of the Russian annulment judgment would violate Dutch policy5 and that the Russian courts were “not independent or impartial” in most instances”. Respectfully, who is the Dutch court to affirm that Russian courts, or any other court, is independent or not? Is it not acting as if it were an appeal court? That is not giving “too much power” to the second country court? What is “Dutch Policy”? Who does determine the “Dutch Policy”? Is the “Dutch Policy” enough to enforce an award that was annulled?

3. Nothing can be unlimited; We cannot pretend an enforcement of an award to be against everything. If we assume that the Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit theory may not apply in arbitration, we are also assuming the “immortality” of the award, because anyway if it is impossible to enforce the ward in one country, it will be enforcing in another one. We have, in the beginning, a lot of possibilities. At least one country, among the 157 ones that are part of the New York Convention will enforce the award.

4. The parties have the duty to choose a neutral seat. As we can see, Yukos, Pemex, and Chromalloy are cases that had the place of the seat of the tribunal in the place of the origin of one of the parties. If we assume that the courts of the seat are taking national public policy and the protection of local interests to annul the award, then what the parties must do is to select a neutral seat for the arbitration.

5. In addition, saying that we can enforce an award that was annulled in the seat of the tribunal contradict the power that the parties gave to the national court when they selected the seat. It is going against their decision. Every single thing in life has a risk. Arbitration is not an exception: The risk that the parties take when they select the seat is giving the court of the place of the seat the power to decide about the final award. That is why the parties must be very careful when they select the seat.

6. Moreover, national courts play a potentially important policing role in this regard. Most jurisdictions have committed their courts to do all that is reasonably necessary to support the arbitral process. Stopping the enforcement of potential injustice awards is part of the justice that also the Arbitration procedure looks for. Both, judges and arbitrators go in the same direction, avoiding injustices.

7. In addition, there are plenty of good, rational and pro arbitration judges in each origin country. We cannot assume that all judges are going to annul the arbitration awards. I am happy with the “ratio” that The District of Columbia Circuit Court presented in one case that happened in my country, Colombia. In TermoRio S.A.E.S.P. and LeaseCo Group, LLC. Electranta S.P., a tribunal had issued an award in excess of USD 60 million in favor of TermoRio. Colombia’s court set aside the award on the ground that the arbitration clause violated Colombian law. The US court hell, “[r]ecognition and enforcement may be refused if an award has been set aside by competent authority … [i]t must take much more than a mere assertion that the judgment of the primary state offends the public policy of the secondary State to overcome a defense raised under Article V(1)(e).” Even if the US court do not totally exclude the possibility to enforce an award that was set aside in the origin country, I am glad with the limitation that it did to the theory of violation of the “public policy” as support to enforce an award in the secondary country.

8. Finally, the judge is limited to the procedure and thus, he is no able to see the substance. We know that having separated procedure and substances is difficult because both go together. However, I believe that most of the judges can find a balance, and that with rationality and clear boundaries, judges will ensure justice, that in the end it is what arbitrators, judges and the parties want.

Position for resolve the problem

In addition to the above arguments that support my position, I think that the arbitration community should understand the idea that judges “complement” the arbitration procedure. As humans, arbitrators make mistakes, mistakes that could create enormous damages for the parties. To avoid that, judges would be the complement of the arbitration procedure and its guardians.

On the other hand, judges should understand the importance of arbitration as the way to promote their country for future investments and the way to lighten the workload.

In addition, I found that the debates around the interpretation of the Article V(1) (e) are focused on the power of the judges, on the power of the arbitrators, and/or the power of the award under the New York Convention, but they are not focused on the same goal that arbitrators, judges and the Convention have in common: Justice.

The New York Convention was created for the facilitation of the fast and efficient enforcement of arbitral awards. It goes together with the idea of justice. It is not about egos or be for or against arbitration. It is about justice. We all have the duty to interpret the Article V (1) (e) under the principle of the good faith and justice, not as the end of arbitration.

Finally, if the parties want to avoid greater uncertainty and this discussion they shall agree, in the arbitration clause, a waiver to seek set aside the final award. Recently, the Swiss Supreme Court held, in the case The Republic of Croatia v. MOL, PCA, that the parties had “validly waived their right to challenge an international arbitral tribunal’s award in their arbitration agreement”. The arbitration clause’s provision held that “[t]here shall be no appeal to any court from awards rendered hereunder”. The Swiss Court affirmed that it provision constituted a valid waiver of the right to seek set-aside of the award rejecting the Croatia’s argument that the waiver was limited to full-blown appeals, rather than actions to set aside or annul an arbitral award.

Conclusion

Dues the above-mentioned reasons, the Article V.1 (e) of the Convention must be interpreted under the principles of the consent of the parties, good faith and justice. Therefore, if the courts of the place where the award was rendered set aside it, it ceased to exist and consequently the award cannot longer be enforced elsewhere.

List of references

- Marike Paulsson, The 1958 New York Convention in Action. 195.

- E generally Georges R. Delaume, Reflections on the Effectiveness of International Arbitral Awards, 12 J. INT’L ARB. (1995) (relating the notion of final and binding effect of an award to the overarching effectiveness of international arbitration)

- Marike Paulsson, The 1958 New York Convention in Action. 195.

- Marike Paulsson, The 1958 New York Convention in Action. 205

- Marike Paulsson, The 1958 New York Convention in Action. 210

Artículos Recientes

¡Ya está disponible el caso! Segunda versión del Concurso Laboratorio de Estrategia Legal #LSL

Invitamos a los estudiantes de pregrado y postgrado de todas las carreras a presentar [...]

Masterclass Legal Operations: Transformando la Función Legal Empresarial de Guardián de Riesgos a Creador de Valor.

El Departamento de Derecho de los Negocios y la Facultad de Administración de Empresas [...]

Conclusión del Proceso de Reforma al Investor-State Dispute Settlement

En la semana del 12 de julio de 2023, durante la sesión anual de [...]

El Departamento de Derecho de los Negocios de la Universidad Externado de Colombia abre convocatoria para la vacante de Asistente de Investigación

¡Sé parte de nuestro equipo de trabajo! Perfil del cargo: Asistente de Investigación Apoyar [...]

Docente del Departamento de Derecho de los Negocios participó en el libro Blanco de la Asociación de Derecho Internacional

La Asociación de Derecho Internacional (ADI), una de la organizaciones más antiguas y prestigiosas [...]

CRYPTO IN COLOMBIA: PROSPECTIVE 2022

By: Daniel Peña Valenzuela The volatility of the main cryptocurrencies seems to be once [...]

Convocatoria de Monitores.

El Departamento de Derecho de los Negocios se complace en anunciar la apertura para [...]

¿Se avecina una regulación de la Franquicia por parte del Gobierno? ¿O lo impedirá la Corte Constitucional?

Por: Juan Miguel Álvarez* y Diana Marcela Araujo* En diciembre del 2020, el congreso [...]

Publicación del libro “Perspectiva de los Tratados Bilaterales de Arbitraje en Colombia: viabilidad y desafíos”

Sin duda alguna, el arbitraje ha ganado una gran popularidad como método de resolución [...]

Curso de verano en Arbitraje Nacional e Internacional y Amigable Composición

El Departamento de Derecho de los Negocios se complace de anunciar este curso de [...]

EL JUEZ TERMINATOR 2

¿El juicio final? Por Nicolás Lozada Pimiento, CEO de Redek y Profesor Titular de [...]

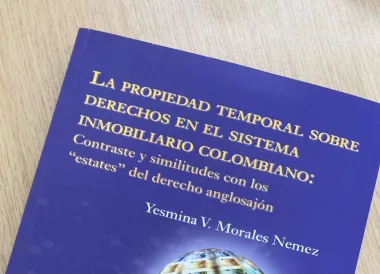

Lanzamiento del libro “La propiedad temporal sobre derechos en el sistema inmobiliario colombiano: Contraste y similitudes con los “estates” del derecho anglosajón”

El Departamento de Derecho de los Negocios se complace en hacer partícipe a toda [...]